America in context

Environment: A Book That Changed a Nation

A shy, unassuming scientist and former civil servant, Rachel Carson love of nature and love of writing compelled her in 1962 to publish Silent Spring, the book that awakened environmental consciousness in the American public and led to an unprecedented national effort to safeguard the natural world from chemical destruction.

A Book That Changed a Nation

Michael Jay Friedman

In 1992, a panel of notable Americans offered their choices for the single book published during the previous half century that most profoundly influenced the thoughts and actions of humankind. More panelists cited Rachel Carsons Silent Spring than any other title.

Silent Springs lasting power to inspire flows less from Carsons diligent research-even before publication, critics attacked some of her findings--but rather from its elegant prose, effective presentation, and fortuitous timing. Silent Spring focused the attention of millions, in America and then throughout the world, on an idea they were increasingly prepared to consider: that the indiscriminate use of pesticides threatened profoundly both the health of mankind and that of the world in which he lived.

As Yale University historian Daniel J. Keveles has written: "Carsons book probably did more than any other single publication or event to set off the new environmental movement that emerged in the Sixties."

Only a few works have similarly catalyzed American public opinion as a force for change. Carsons impact compares with that of Thomas Paine, whose 1776 pamphlet Common Sense spurred popular support for American independence from Great Britain. American works of comparable influence might also include Uncle Toms Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe, which energized the struggle against slavery, and The Jungle (1906) by Upton Sinclair, which described unhealthful meatpacking practices and sparked the passage of federal food inspection laws.

Toxic Connections

Rachel Carson had long suspected that increasingly powerful chemical pesticides were being used carelessly, and she feared their impact on the environment. In 1958, Carsons friends Stuart and Olga Huckins propelled her investigations. The Huckinses owned a two-acre bird sanctuary near Duxbury, Massachusetts. After the government doused it with pesticides as part of a mosquito eradication program, many native songbirds perished, their nesting places, ponds, and birdbaths contaminated.

For the next four years, Carson consulted with scientific experts. "The more I learned about the use of pesticides, the more appalled I became," she later said. "I realized that here was the material for a book. What I discovered was that everything which meant most to me as a naturalist was being threatened, and that nothing I could do would be more important."

Carson concluded that in a natural environment of interconnected species, chemicals aimed only at insects or other pests were soon ingested by other organisms and passed up the food chain. After the city of Detroit sprayed insecticide on local elm trees, Carson observed, it subsequently collected the dead bodies of DDT-contaminated robins. The birds had feasted on earthworms that had in turn ingested fallen leaves from the sprayed trees.

"As few as 11 large earthworms can transfer a lethal dose of DDT to a robin," Carson wrote. "And worms form a small part of a days rations to a bird that eats 10 to 12 earthworms in as many minutes."

About half of Carsons manuscript appeared in June 1962 over three consecutive issues of the New Yorker magazine. The excerpts ignited a national controversy. The U.S. Department of Agriculture received many letters expressing "horror and amazement" that DDT and other chemical "elixirs of death" were in common use.

Asked whether the U.S. government was investigating the use of DDT, President John F. Kennedy replied, "Yes ... particularly since Miss Carsons book."

Much of the chemical industry saw Silent Spring as a threat. "Our members are raising hell," one pesticide trade association divulged. The New York Times reported that "some chemical concerns have set their scientists to analyze Miss Carsons work line by line."

But critics could find little factual error. Criticism focused instead on how Carson dramatized her concerns and minimized the real benefits of pesticides in assuring plentiful, affordable food supplies. "She tries to scare the living daylights out of us," wrote the New York Times book reviewer of Silent Spring, "and, in large measure, succeeds."

The publicity stoked public demand for the book. Silent Spring was published in complete book form in September 1962, chosen as the Book-of-the-Month Clubs October selection, and quickly emerged as a runaway bestseller. The CBS television network broadcast an hour-long documentary about the book.

A Larger Truth

As Carsons critics understood, Silent Spring possessed an emotional power that overcame objections to specific bits of Carsons argument. Even as Time magazine argued that "many of the scary generalizations ... are patently unsound," most readers concluded that Carson understood and depicted accurately a larger truth: that mankinds growing reliance on deadly chemicals carried real and not fully understood costs.

Few readers could resist Carsons literary skill. "There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings," she wrote:

Then a strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change. ... There was a strange stillness. ... The few birds seen anywhere were moribund; they trembled violently and could not fly. It was a spring without voices. On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of scores of bird voices there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.

In May 1963, President Kennedys Science Advisory Committee released a 43-page report that called for limits on the use of pesticides. Kennedy immediately ordered implementation of its recommendations, which included an end to some Department of Agriculture spraying programs and a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review--"as rapidly as possible"--of tolerance levels for pesticide residue in the food supply. The report also acknowledged that "until publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, people were generally unaware of the toxicity of pesticides."

Silent Spring proved a hugely significant catalyst for measures protecting the natural environment in the United States and beyond. In 1972, the FDA banned nearly all uses of DDT in the United States (many believe that, properly used, the chemical affords benefits in malaria-plagued nations), and new laws limited commercial pesticide use to properly trained "certified applicators."

Rachel Carson lived only one and a half years beyond Silent Springs publication, not long enough to witness its full contribution to the rebirth of environmental consciousness, but enough to know she had made a difference. "I have felt bound by a solemn obligation to do what I could," she wrote a friend. "But now I can believe that I have at least helped a little."

Additional readings:

Rachel Carson: Pen Against Poison, U.S. Department of State, Bureau of International Information Programs, March 2007

About the Author:

Michael Jay Friedman is a staff writer with the U.S. State Departments Bureau of International Information Programs.

Recently on America in context

The American Identity

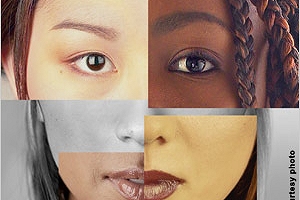

"American" is an inclusive term and we apply it generously, because becoming an American is about embracing a set of ideals and pursuing a way of life, rather than embodying a particular ethnic group, religion, or culture. And though we are a mobile society, a connection or bond to place, often the neighborhood or town in which we grew up, is important to us.

"American" is an inclusive term and we apply it generously, because becoming an American is about embracing a set of ideals and pursuing a way of life, rather than embodying a particular ethnic group, religion, or culture. And though we are a mobile society, a connection or bond to place, often the neighborhood or town in which we grew up, is important to us.

Philanthropy in the U.S.

How did philanthropy come to play such a key role in providing essential elements of life in the United States? According to the Council on Foundations, charitable giving in the United States has strong roots in religious beliefs, in the history of mutual assistance, in the democratic principles of civic participation, in pluralistic approaches to problem solving, and in American traditions of individual autonomy and limited government.

How did philanthropy come to play such a key role in providing essential elements of life in the United States? According to the Council on Foundations, charitable giving in the United States has strong roots in religious beliefs, in the history of mutual assistance, in the democratic principles of civic participation, in pluralistic approaches to problem solving, and in American traditions of individual autonomy and limited government.

U.S. Elections 2008: How the Internet Is Changing the Playing Field

The Internet has revolutionized communication over the last decade, bringing people together for every imaginable purpose. The author discusses several online innovations that have come into play in the political arena, as candidates and — even more creatively — citizens use technology to influence voters.

The Internet has revolutionized communication over the last decade, bringing people together for every imaginable purpose. The author discusses several online innovations that have come into play in the political arena, as candidates and — even more creatively — citizens use technology to influence voters.