America in context

John Updike Explores How Art Mirrors America’s Soul

John Updike, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose prolific output of novels, short stories, poems and essays has made him one of the most celebrated American writers now living, is perhaps best known as a chronicler of life in America’s small towns and affluent suburbs. As such, he is a longtime observer of his nation’s quirks, customs and tribal rituals, and an interpreter of a broad cultural landscape that defines the United States as surely as its geography does.

So when Updike arrived in Washington to deliver the 2008 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, an event sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) on May 22, it seemed only logical that he would structure his remarks around the question “What is American about American art?”

The question, he said, “has often arisen,” but it is less fashionable than it used to be, since any comprehensive survey of American achievement in the arts “inevitably gravitate[s] … to that least hip of demographic groups, white Protestant males of northern European descent.”

The question, he said, came to mind as he contemplated a new program -- “Picturing America” -- that will bring poster reproductions of 40 significant American artworks to classrooms and public libraries throughout the United States. Launched by the NEH in partnership with the American Library Association, the program aims to introduce U.S. students to their country’s artistic heritage through paintings, sculpture, architecture, fine crafts and photography that help illuminate the nation’s character, ideals and aspirations.

“Picturing America” features works as varied as Alexander Gardner’s haunting photograph of a war-weary President Abraham Lincoln, sitting for the camera just three months before his assassination in 1865; Mary Cassatt’s 1893-1894 oil painting The Boating Party, depicting a tranquil family group enjoying an outing on a lake; Italian immigrant Joseph Stella’s painting Brooklyn Bridge (circa 1919-1920), a tribute to the dynamism of modern life and the machine age; Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural masterpiece Fallingwater (1935-1939), a boldly contemporary dwelling suspended above a waterfall; and Romare Bearden’s collage The Dove (1964), a bustling cityscape that explores the urban African-American experience.

While tipping his hat to the “sensitively diverse set of 40 artworks” included in “Picturing America,” Updike said his lecture -- titled “The Clarity of Things” -- would focus on the much-derided “dead white males” whose contributions to the U.S. artistic canon have profoundly shaped the public’s understanding of America’s history and cultural traditions. Despite having fallen out of favor “in this age of diversity and historical revision,” these “thin-lipped patriarchal persons” cannot be ignored by anyone who seeks to appreciate how artists have shaped the United States, from Colonial times to the present day, said Updike.

AN EMERGING NATION AND ITS ARTISTS

According to Updike, the first great American painter was John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), born in Boston to Irish immigrant parents. Copley began his career in Boston as a teenage prodigy, painting oil portraits that captured a subject’s likeness with virtuosic realism. Copley’s attention to detail, and his “preternatural skill in rendering fabrics” (an important quality, since a sitter’s clothing was an indicator of social rank), soon established him as “the supreme portraitist not only in New England but in all the Colonies,” Updike said.

CONSTRUCTING AN IDENTITY: THE PAST AS PROLOGUE

Updike also cited several other notable artists from the “Picturing America” series, such as Grant Wood, whose oil painting The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931) offers an aerial view of Revere’s famous exploit, portrayed “with a flavor of parody; the village is toylike, … [and] Revere’s steed is stretched out in the position of a hobbyhorse.” A similar folksiness informs Thomas Hart Benton’s 1975 mural Origins of Country Music, “limned in Benton’s usually wiry, restless lines.” In Updike’s view, “such cartoonishness genially asks for a suspension of disbelief while it presents not so much an American scene as a rendering of America’s self-image,” an affectionate nod to national myths and tall tales.

Walker Evans’ 1919 photograph of the Brooklyn Bridge, shown as an engineering marvel whose lines “gracefully resist the downward pull of gravity, as the pointed arches of a Gothic cathedral do,” records the industrialization of America, said Updike. Not so the homespun scenes painted by Norman Rockwell, whose works appeared on the covers of the Saturday Evening Post for decades. Rockwell came to be regarded as a beloved national treasure for his pictorial representations of core American values; most of his paintings are wholesome vignettes that reveal the warmth, integrity and humor of Americans from all walks of life.

Updike gives Rockwell his due, pointing to the artist’s oil painting Freedom of Speech (1943), “rendered without visible brushwork, the hallmark of a painterly manner.” In this iconic painting, conceived as a tribute to democracy in action, “attention is focused from all sides” on the central figure, a man who rises to speak at a town meeting.

More information about the “Picturing America” program is available on the NEH Web site.

About Picturing America

Great art speaks powerfully, inspires fresh thinking, and connects us to our past.

Picturing America, an exciting new initiative from the National Endowment for the Humanities, brings masterpieces of American art into classrooms and libraries nationwide. Through this innovative program, students and citizens will gain a deeper appreciation of our country’s history and character through the study and understanding of its art.

The nation’s artistic heritage—our paintings, sculpture, architecture, fine crafts, and photography—offers unique insights into the character, ideals, and aspirations of our country.

Picturing America, a far-reaching new program from the National Endowment for the Humanities in cooperation with the American Library Association, brings this vital heritage to all Americans.

By bringing high-quality reproductions of notable American art into public and private schools, libraries, and communities, Picturing America gives participants the opportunity to learn about our nation’s history and culture in a fresh and engaging way. The program uses art as a catalyst for the study of America—the cultural, political, and historical threads woven into our nation’s fabric over time.

Collectively, the masterpieces in Picturing America, used in conjunction with the Teachers Resource Book and program Web site, help students experience the humanity of history and enhance the teaching and understanding of America’s past.

About Picturing America from Humanities, September/October 2007, Volume 28/Number 5

By Lauren Monsen

Staff Writer

Recently on America in context

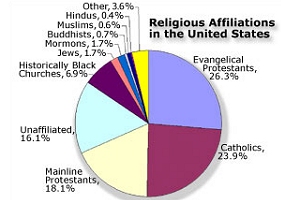

U.S. Religious Landscape Is Marked by Diversity and Change

Religious affiliation among U.S. residents best can be described as "diverse and extremely fluid," according to a new poll conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life.

Religious affiliation among U.S. residents best can be described as "diverse and extremely fluid," according to a new poll conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life.

American Identity: Ideas, Not Ethnicity

Since the United States was founded in the 18th century, Americans have defined themselves not by their racial, religious, and ethnic identity but by their common values and belief in individual freedom.

Since the United States was founded in the 18th century, Americans have defined themselves not by their racial, religious, and ethnic identity but by their common values and belief in individual freedom.

Immigration and U.S. History

Millions of women and men from around the world have decided to immigrate to the United States. That fact constitutes one of the central elements in the country's overall development, involving a process fundamental to its pre-national origins, its emergence as a new and independent nation, and its subsequent rise from being an Atlantic outpost to a world power, particularly in terms of its economic growth. Immigration has made the United States of America.

Millions of women and men from around the world have decided to immigrate to the United States. That fact constitutes one of the central elements in the country's overall development, involving a process fundamental to its pre-national origins, its emergence as a new and independent nation, and its subsequent rise from being an Atlantic outpost to a world power, particularly in terms of its economic growth. Immigration has made the United States of America.